December 31, 2012

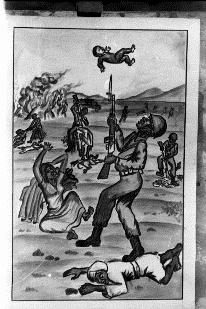

The colonial regime has actively pursued the policy of destroying the schools and hunting down teachers, while in the area under its control and especially in the cities, it has diffused a colonialist culture, lowered the quality of education and attempted to corrupt the youth, in order to prevent the new generation from gaining the proper education. The negative impact of this policy has grown with time.

The war and the attendant disruption of life, the existence of many areas in the county where schooling had never been introduced and the consequent cultural gap among different sectors of the population have been obstacles to the balanced development of the society and participation in the liberation struggle. As a result, the creation of a wide educational opportunity for Eritrean children and youth was given high priority in the educational program. To this end, schools, up to middle school level, were opened in all liberated and semi-liberated areas, and especially in those areas that had previously been denied this opportunity. The effort made to expand and upgrade the “revolution school” is one example. Steps were also taken to establish and expand the technical school in order to train personnel in different trades for the purpose of national development and nation-building.

The more formulation of an educational policy and program, or possessing the will to implement such a plan is inadequate by itself. Curricula have to be prepared, qualified teachers have to be made available, teaching and training aids made available, schools constructed in safe areas and provided with necessary equipment. The EPLF and its department of education had set up a national education system, which did not previously exist. Taking into consideration the limited professional competence, and paucity of educated personnel, and the complex national characteristics, the number of books which have been produced, while not small, was far from adequate. The requirements of the war and other revolutionary tasks were further reducing the already inadequate number of teachers with pedagogical training. The problem was further aggravated by the drain of educated man power due to emigration.

To surmount this problem, steps were taken to recruit and train teachers and, at the same time, the participation of students of the “Revolutionary School” and those who could teach from within the masses was actively promoted. But the number and competence of teachers remained inadequate even for the requirements of the initial period. The shortage of printing equipment, papers, ink, and therefore, of textbooks also militates against the full implementation of the curriculum, while the non-availability of exercise books, pens, and pencils, black boards, desks, chairs as well as laboratory and work shop equipment was critical. The vigorous efforts of the printing press and the department of construction and manufacturing to solve these problems by allocating man power and equipment and utilizing domestic inputs produced tangible results. Nevertheless, the remaining tasks were formidable.

The education of Eritrean refugee was another task which could be neglected; nearly half a million Eritreans were living as refugees, most of them in the Sudan. Among them were many literates and intellectuals. For the rest educational opportunities were practically non-existent, though they were limited in some countries. As, sooner or later, these refugees will play a big role in national reconstruction, the EPLF has, always been interested in providing them with education, particularly those in the Sudan. But the policy of the Sudanese government and the role of the UNHCR were hampering the endeavor. In general, the problem posed by the second class status of Eritrean refugees as well as, political, economic and social pressures had been compounded by obvious disinterest on the part of the youth.

Aware of the limitation of its resources and the constraints of the prevailing conditions, the EPLF worked to involve friendly and interested parties in the contribution of educational materials and equipment. Many of these have shown interest and provided support.

What type of education should we have? The Eritrean people speak different languages and have different cultural levels. In the context of a people with such a diverse composition, it was essential that educational policy should be clearly articulated, especially with respect to languages, and promoting voluntary national unity and nation-building.

Taking this as its central point, the educational policy of the EPLF has emphasized the following fundamental principles. Each nationality has the right to develop its spoken and written language and to use it in its internal administration. The educational and cultural gap between Eritrean nationalities and regions should be narrowed and leveled by giving greater educational opportunities to the regions that have lagged behind. The language of the majority or more developed nationality or segment of the society should not be imposed on others. The educational policy should foster national development and nation building and should not become an instrument for dividing and disintegrating the people.

On the basis of these principles the EPLF adopted the following educational policy. Each citizen should be instructed at the elementary school level in his/her language. This is done not out of desire to foster many languages but because it is easier and more efficient. English should be taught as a language in all elementary schools to enable all Eritreans entering middle school to acquire proficiency in the language which will be used as a medium of instruction at that stage.

The content of the education given at the elementary grade should be uniform in all languages. In addition, at the elementary level, students should study Arabic, Tigrina or other languages of their choice. At the middle school stage, English is the medium of instruction for all and Arabic, Tigrina or any other Eritrean language will be taught as optional subjects. At the higher levels English will remain the medium of instruction while language training in Arabic, Tigrigna and others will continue on an elective basis.

The language question is one which bankrupt forces persistently strive to exploit. These elements claim the EPLF’s educational policy is anti-Arabic and seeks to make Tgrigna paramount. Their obvious intention is to fan religious sentiments in order to isolate the EPLF. Although those who know and speak Arabic are not all adherents of Islam, and Arabic as a language is of concern not only to Muslims, it is true that Muslims have spiritual ties with Arabic. Besides there are fears of Tgrigna language domination on the part of the other nationalities, as Tgrigina-which has its own script is the language of a predominantly Christian nationality, which is not only the largest Eritrean nationality, but for reason already explained, has a relatively more developed culture. The EPLF’s education policy, however, treats Tgrigina on a par with other languages, to be employed as a medium of instruction at the elementary school level on those who speak it. With respect to Arabic, the EPLF believes that it is a language which all Eritrean should learn and has consistently promoted its use and Arabic language instruction. It does this not because Arabic is the national language or the language of the Rashaida nationality, but because it serves as the language of interaction both among Eritreans and between Eritreans and the Arab people of our region. Despite EPLF’s efforts, however, the use of Arabic has not spread as desired due to obvious technical constraints. The EPLF rejects the effort of opportunists and elements with narrow political objectives who exploit religious and linguistic differences to establish for themselves a social base which they can freely manipulate and strive to create, in the Eritrea today and that of the future, a sectarian political atmosphere which engenders conflict by promoting a system of education which segregates schools on the basis of language.

A related question raised by the same elements and for similar goals was the role of religion in education. The EPLF program unequivocally states that each citizen has the right of religious belief. Religious instruction is allowed and religious institutions will not be prevented from carrying out their spiritual functions. However, all attempts to use religion as a political and to infuse religion in the educational system in order to divide the people are contrary to the interest of national unity and nation-building and therefore unacceptable.